Braille is Not a Different Language

Grade 1 Braille

Grade 2 Braille

Grade 3 Braille

Braille Transcription vs. Braille Translation

A Closer Analysis of Braille

More Information on Braille

Braille is Not a Different Language

What is braille, you ask? Braille is a code. It is a system of reading and writing a specific language without the use of sight. Braille enables people with blindness and visual impairments to read through touch.

Though Louis Braille created the tactile reading and writing system we use today, he drew inspiration from a French army captain named Charles Barbier who developed a similar code. Barbier created a nonverbal communication system so his officers could read battle commands during the night without the use of candlelight. In the late 1800s, Louis Braille refined Barbier’s system and created the foundation for today’s braille code.

Thankfully braille is a code and not a language. Because it’s a code, we can transcribe braille into several dialects including English, Spanish, French, German, and Italian.

For many languages, including English, there are different versions, or “grades,” of braille.

Grade 1 Braille

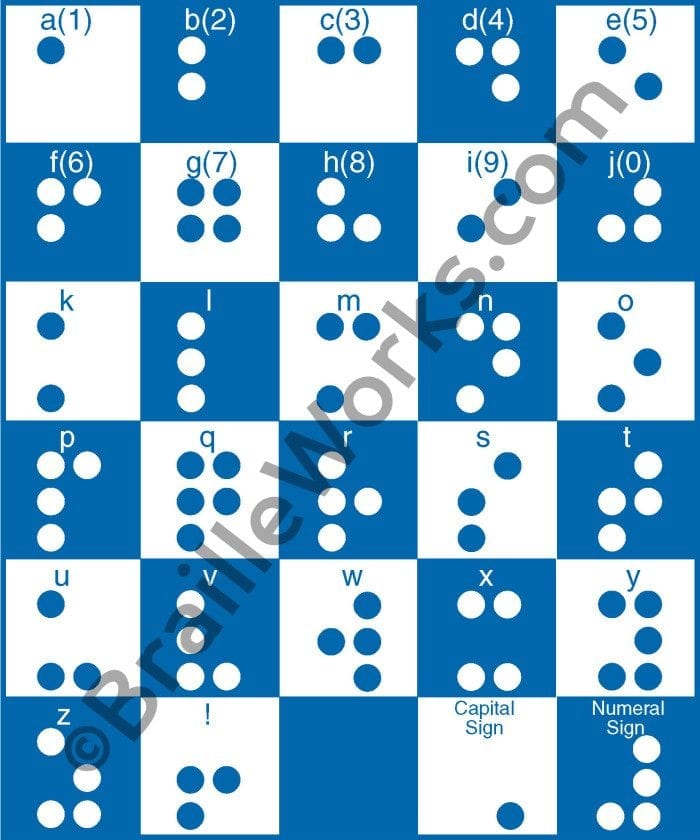

Grade 1 braille is a letter-for-letter substitution of its printed counterpart. This is the preferred code for beginners because it allows people to get familiar with, and recognize different aspects of, the code while learning how to read braille.

English grade 1 braille consists of the 26 standard letters of the alphabet as well as punctuation.

Grade 2 Braille

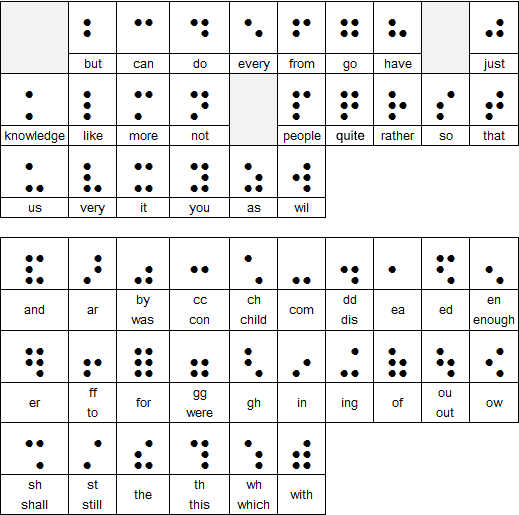

The literary braille code, grade 2, uses “contractions” that substitute shorter sequences for the full spelling of commonly-occurring letter groups. The contractions are similar to English print contractions, like “cannot” versus “can’t”, in the way that a word is shortened. For example, “the” is usually a single character in braille.

We use this type of braille code for a few reasons.

First, a standard braille cell is large. It’s approximately the equivalent of 29pt Arial font. That means that one page of print can easily turn into three pages of braille. Contractions help reduce the number of characters and thereby reduce the overall size of a document.

Second, reading and writing braille can be time-consuming. By implementing contractions, it takes less time to do both.

Grade 2 braille is the most commonly used form of braille code and is found in books, public signage, and restaurant menus to name a few. It consists of the 26 standard letters of the alphabet, punctuation, and contractions.

Grade 3 Braille

Grade 3 is the last, and certainly least (used), form of literary braille code used within the blind community. Considered braille “shorthand,” this code often compresses entire words into just one or a few characters. There is no official standardization for grade 3 braille and, therefore, official publications do not use it. Instead, it most often appears in personal letters, diaries, and notes.

Braille Transcription vs. Braille Translation

Braille transcription is the process of converting printed text to braille. The translation of braille is the process of converting one language’s braille code into another. People sometimes confuse braille transcription with braille translation. Unfortunately, this conveys a misleading belief that braille is a different language rather than merely a different system of reading and writing a specific language.

A Closer Analysis of Braille

Six Dots

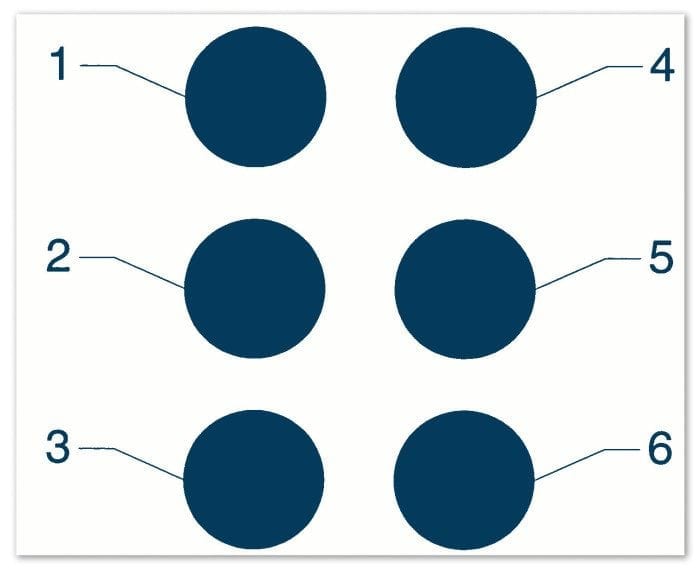

Six dot positions make up each braille character or “cell”. These dot positions form a rectangle composed of 2 columns with 3 dots in each column. A single dot or any combination of dots may be raised at any of the 6 positions. Counting spaces, in which no dots appear, there are 64 English braille combinations in total. When referencing a braille character, one may describe the positions where dots are raised. Each dot within a cell has a number. Starting in the upper left and moving down, the dots are universally numbered 1 through 6 as seen in the image below.

For example, dots 1-3-4 would describe a cell with three dots raised; the top and bottom cells of the left column and the top cell of the right column.

Indicators

Because the 64 distinct characters are never enough to cover all possible print signs and their variations, it is necessary to use multi-character sequences for some purposes. Often we use certain characters as “prefixes” or “indicators” that affect the meaning of subsequent cells. For example, when a dot 6 falls before a letter, the reader knows it is a capital letter. Without a dot 6, the reader knows it is a lower case letter. In another example, dots 3-4-5-6, called the “numeric indicator”, tells the reader to interpret certain following letters (A through J) as numbers. There is then another character or a space to tell the reader they are switching back to letters.

More about the braille cell

Dot height, cell size, and cell spacing are always uniform. Significant characteristics of the text, such as italics used for emphasis, must be handled by indicators in braille. An exception to that formatting, such as the centering of main headings, is commonly used in braille in much the same way and for most of the same purposes as in print.

Notation systems other than natural languages such as music, mathematics, and computer programming use separate braille codes.