History of Braille

What is Braille?

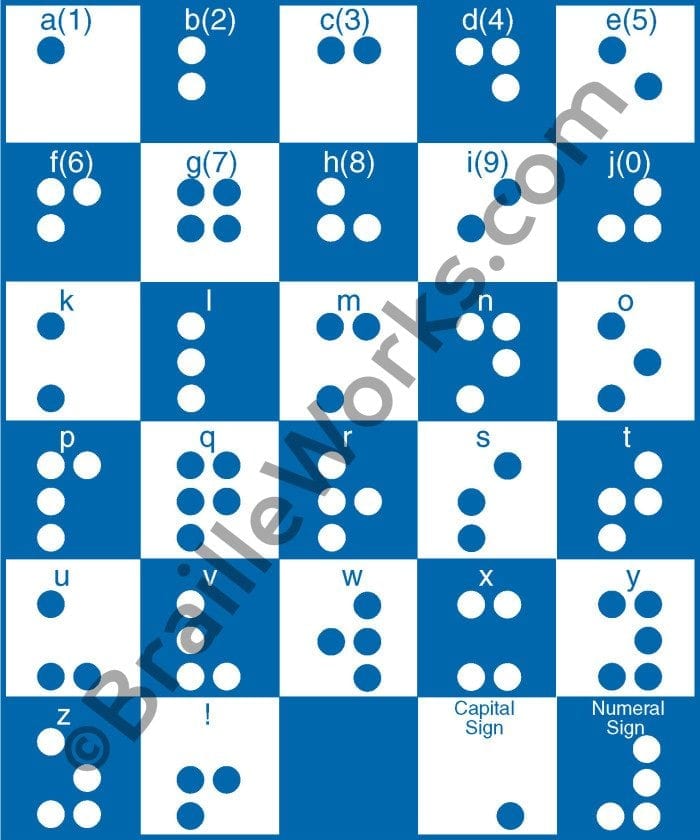

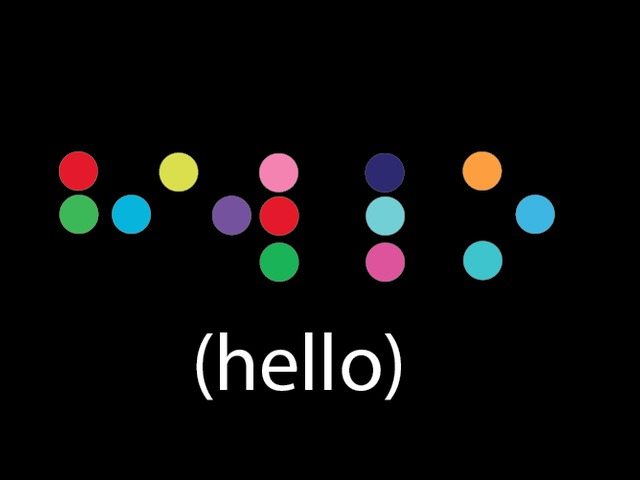

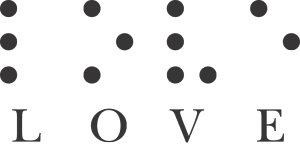

Braille is a system of touch reading and writing for blind persons in which raised dots represent the letters of the alphabet. It also contains equivalents for punctuation marks and provides symbols to show letter groupings.

People read braille by moving the hand or hands from left to right along each line. The reading process usually involves both hands, and the index fingers generally do the reading. The average reading speed is about 125 words per minute. But, greater speeds of up to 200 words per minute are possible.

By using the braille alphabet, people who are blind can review and study the written word. They can also become aware of different written conventions such as spelling, punctuation, paragraphing and footnotes.

Most importantly, braille gives blind individuals access to a wide range of reading materials including recreational and educational reading, financial statements and restaurant menus. Equally important are contracts, regulations, insurance policies, directories, and cookbooks which are all part of daily adult life. Through braille, people who are blind can also pursue hobbies and cultural enrichment with materials such as music scores, hymnals, playing cards, and board games.

Various other methods have been attempted over the years to enable reading for the blind. However, many of them were raised versions of print letters. It is generally accepted that the braille system has succeeded because it is based on a rational sequence of signs devised for the fingertips, rather than imitating signs devised for the eyes.

Charles Barbier’s “Night-Writing”

The history of braille goes all the way back to the early 1800s. A man named Charles Barbier who served in Napoleon Bonaparte’s French army developed a unique system known as “night writing” so soldiers could communicate safely during the night. As a military veteran, Barbier saw several soldiers killed because they used lamps after dark to read combat messages. As a result of the light shining from the lamps, enemy combatants knew where the French soldiers were and inevitably led to the loss of many men.

Barbier based his “night writing” system on a raised 12-dot cell; two dots wide and six dots tall. Each dot or combination of dots within the cell represented a letter or a phonetic sound. The problem with the military code was that the human fingertip could not feel all the dots with one touch.

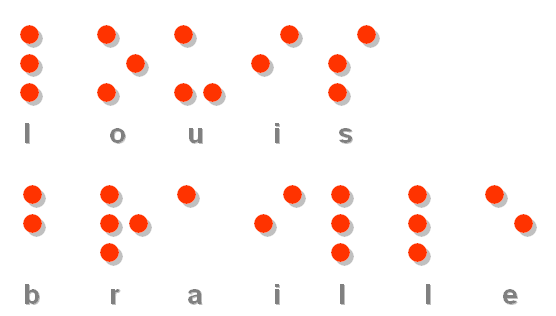

Enter Louis Braille

Louis Braille was born in the village of Coupvray, France on January 4, 1809. He lost his sight at a very young age after he accidentally stabbed himself in the eye with his father’s awl. Braille’s father was a leather-worker and poked holes in the leather goods he produced with the awl.

At eleven years old, Braille found inspiration to modify Charles Barbier’s “night writing” code in an effort to create an efficient written communication system for fellow blind individuals. He enrolled at the National Institute of the Blind in Paris one year earlier. He spent the better part of the next nine years developing and refining the system of raised dots that we now know by his name, Braille.

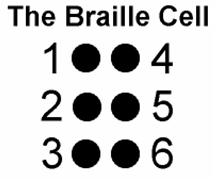

After all of Braille’s work, the code was now based on cells with only 6-dots instead of 12 (like the example shown below). This crucial improvement meant that a fingertip could encompass the entire cell unit with one impression and move rapidly from one cell to the next. Over time, the world gradually accepted braille as the fundamental form of written communication for blind individuals. Today it remains basically as he invented it.

However, there have been some small modifications to the braille system, particularly the addition of contractions representing groups of letters or whole words that appear frequently in a language. The use of contractions permits faster braille reading. It also helps reduce the size of braille books, making them much less cumbersome.

Braille passed away in 1853 at the age of 43, a year before his home country of France adopted braille as its’ official communication system for blind individuals. A few years later in 1860, braille made its way “across the pond” to America where it was adopted by The Missouri School for the Blind in St. Louis.

Timeline of advancements in braille

- 1869 – We see the introduction of braille code.

- 1932 – Braille code was adopted as the standard English code.

- 1932 to the late 1960s – Most students with blindness were taught to read and write braille.

- 1973 – The Rehabilitation Act allowed students with a visual impairment to attend local public schools. Braille was not taught to all students in public schools.

- 1975 – Congress passed public law 94-142 called The Education of All Handicap Children Act, which includes the Free and Appropriate Education Act (FAPE).

- 1991 – The National Literacy Act defines “literacy” as “an individual’s ability to read, write, and speak in English, and compute and solve problems at levels of proficiency necessary to function on the job and in society to achieve one’s goals and develop one’s knowledge and potential.”

- 1995 to 1996 – Approximately 54,000 students were legally blind, but only around 4,700 students were taught braille in public schools.

- 1997 – A revision to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) states: “(iii) in the case of a child who is blind or visually impaired, provide for instruction in Braille and the use of Braille unless the Individualized Education Program (IEP) team determines, after an evaluation of the child’s reading and writing skills, needs, and appropriate reading and writing media (including an evaluation of the child’s future needs for instruction in Braille or the use of Braille), that instruction in Braille or the use of Braille is not appropriate for the child.” 20 U.S.C. 1414(d)(3)(B)(iii).

- 1997 – The IEP teams rarely determined braille as the appropriate pathway to blind literacy. This was mainly due to the lack of teachers able to teach braille writing and reading.

- 1999 – Braille instruction was proposed as the pathway to national literacy for students who are blind. Many contested the move as a violation of students’ IEP.

Legacy of Braille Benefits Millions

Louis Braille’s legacy has enlightened the lives of millions of people who are blind. As a result, blind individuals from all over the world benefit from Braille’s work daily. Today, we transcribe braille code in many different languages worldwide. Louis would be very proud to know his creation has given literacy to countless numbers of people over the decades. Consequently, people who are blind can enjoy all the printed-word has to offer just like everyone else. The effect is tremendously empowering and helps them achieve success in school and their careers.

Several groups have been established over the last century to modify and standardize the braille code. Visit the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) for the latest news and developments on braille.

More Braille Resources:

- Braille Alphabet

- Braille is Not its’ Own Language

- Definition of Braille

- Unified English Braille

- Wikipedia – Braille

- Wikipedia – Louis Braille