Mindful of the Underserved Includes People With Visual Disabilities

Published onAmericans are more mindful of civil rights and equality than we were before the era of Social Media. We understand more about the underserved populations based on gender identity, race, socioeconomic status, and some disabilities. But, we are still missing the mark for a large population of people with visual disabilities. People with disabilities are in the protected class—particularly those with visual disabilities. There is a legal difference between the underserved population and people in a protected class.

The term protected class relates to people whose rights are federally protected by laws whereas the underserved population is a blanket term for people who do not have equal access, but they might not be a protected class.

Many Americans with visual disabilities face inequalities in literacy even though they are part of a protected class, as defined by federal laws. This is where businesses and organizations can help bridge the gap, by following the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) guidelines for effective communication.

Literacy Defined

Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. (UNESCO, 2004; 2017).

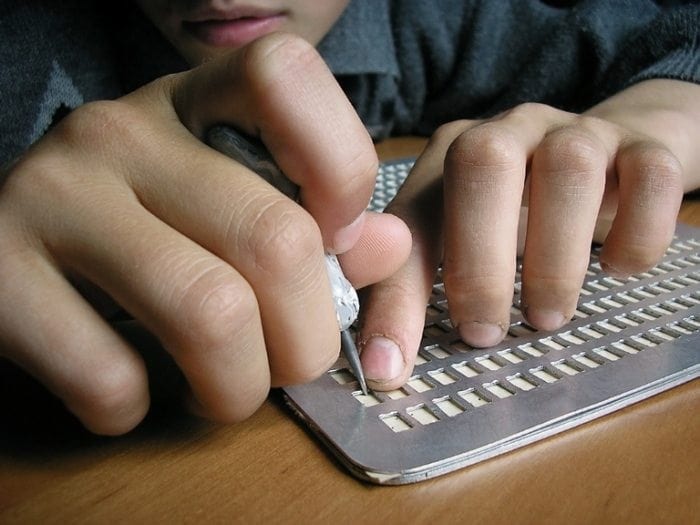

For a person who is blind, the meaning of literacy doesn’t change. Just replace printed materials with braille materials. Reading, writing, and comprehending braille is literacy for someone who is blind. You see, the right to literacy is clear when you read the federal laws.

Literacy, the Inequality Starts at a Young Age

The exclusion of people with visual disabilities begins at a young age. There seems to be a gap in what literacy is, and the question of who is deserving of literacy. Literacy outcomes relate to poverty, wellness, and life expectancy.

Visual Impairment (VI) teachers teach students who are blind braille literacy. However, many school districts have a limited number of VI teachers, if any at all. In a poll taken in 2009 amongst 6,000 students who were blind or visually impaired, only 8.2% identified as being braille literate. In 1960, that percentage was as high as 50%.

The Reality of Equality for People with Blindness and Visual Disabilities

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Title III requires that businesses and organizations provide materials in an accessible format. The ADA states the person with a communication disability can select the accessible document format they require. By not providing this choice, organizations face civil rights violations.

All too often, organizations deny essential information, in an accessible format, to people with vision disabilities. Consequently, not providing accessible documents withholds literacy from people. This, in turn, results in people not making informed decisions regarding their medical wellbeing, insurance needs, financial future, an informed voter, and general civil rights.

How Can A Business Become More Mindful and Purposeful in Equality for All?

Firstly, equality should not be considered a trend or a hashtag. It is a right for people with disabilities in America, and a requirement of doing business in the United States.

Secondly, the best way to make sure the rights of all people are a priority and protected is by asking. Yes, ask clients if they require any additional assistance or an alternative to standard print. This small step can make a difference in someone’s life outcomes. Thus, decreasing poverty, increasing life expectancy, and improving health for many Americans. Lastly, by partnering with a reputable document accessibility company that meets the highest standards in the industry, businesses can be prepared to meet the needs and rights of all people. Because once a business knows better, it can do better.

Categorized in: Accessibility, Informational

This post was written by

Comments are closed here.